How couples can split the mortgage cost and value of the house

When couples buy a house together, the question often arises how to split the mortgage costs. What you should consider.Updated on July 15, 2025

What do you do in a situation like this, when you each have a different income and assets, and you buy a house together? Let’s take a look at your opportunities.

Start with the basics

Start with the basic principle of equality. Yes, you both want a degree of independence, but as partners, you are fundamentally equal. Maybe one does more in the home, the other outside. Perhaps one is a better mother, and maybe the other is a better father.

50-50 is a great starting point – a simple principle. You can go to the notary and agree on any split of the property. But if this is where you are going to live together, raise your kids, and make your home, then don't split hairs. You will come across enough opportunities to disagree.

Bringing in different amounts of equity

But what if you bring in different equity? For example, one partner has saved 30,000 euros and the other 90,000 euros. A simple principle is – if you had your finances separate – to each have a claim on the money that you bring in when you sell the house. I.e., you get your original claim back.

Of course, you can think of all kinds of variations. The most obvious would be to have the equity claim grow with inflation so your claim stays the same in purchasing power terms. Say that inflation is 2.5% per year or 50% over the next 20 years. Then, the claim of the first partner grows from 30,000 euros to 45,000 euros, and the claim by the second partner will grow from 90,000 euros to 135,000 euros.

The argument for this would be that you want to focus on the real value of what you bring in and consider that the house also grows with inflation. You would have to pick an index and specify details. An example of making this concrete is the following:

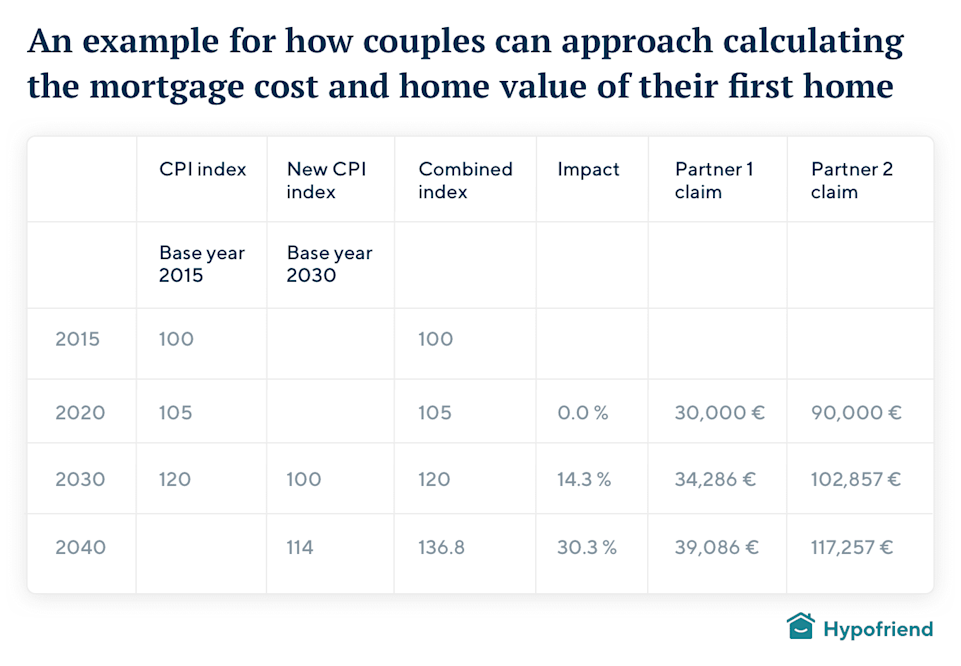

The claim of Partner 1 and Partner 2 will be adjusted with the change in the customer price index (“Verbraucherpreisindex für Deutschland”), the base year 2015, published by the “Statistisches Bundesamt,” starting the month following the purchase of the house and ending at the end of the month the house is sold. If the series is updated to a new index, the new index will need to be multiplied by the ratio of the old index divided by the new index at the time the new index is introduced.

Here, the customer price index (CPI) is the most representative index of consumer prices in Germany. The base year of 2015 helps you identify the specific series. But keep in mind that they will update the series, so the clause quickly gets complex. See the table below for an example:

But honestly, the longer you own that house together, the less it matters that you started off differently. I would keep it simple and appealing to your basic sense of equality.

What about each share in the monthly mortgage payments?

You both have your income. Should one pay more, the other less? Perhaps the easiest solution is to have a household budget, and each pays into that according to what is reasonable. Ability is the first pillar of what is reasonable.

The second pillar is that everyone needs to have enough financial freedom to maintain a sense of self-reliance, independence, or whatever you want to call it. So, each could contribute a percentage of their income, but only if that leaves a minimum to the lowest earner so if the lowest earner becomes unemployed or goes on parental leave (“Elternzeit”) that basic freedom is preserved.

Here, too, you can come up with different and complex principles. My suggestion is to keep it simple and appealing to your basic sense of what is just.

Only one has income?

In many cases, only one of the two partners has an income. I would apply the same principle. Each of you contributes a share of your income (which is zero in the case of the non-earning partner), and each partner gets allocated a minimum.

In this case, that minimum should also reflect the need to build up a savings cushion and (if not somehow provided especially important) to help secure an adequate income during the “retirement” years, i.e., old age.

In the end

In the end, it is just money. Unfortunately, ⅓ of couples do have serious disagreements over money. And in the end, relatively many women end up poor in old age. Therefore, it is important to talk openly (and understandingly) about these issues and be fair and realistic.

My bottom-line advice: Make sure that each of your minimum needs is provided for so you both can be safe and focus on love and happiness.